Today, of course, we are familiar with the specialized membranes and the enormous variety of nerve cell shapes and sizes.

Before the work of Deiters and Ramón y Cajal, both neurons and neuroglia were believed to form syncytia, with no intervening membranes.

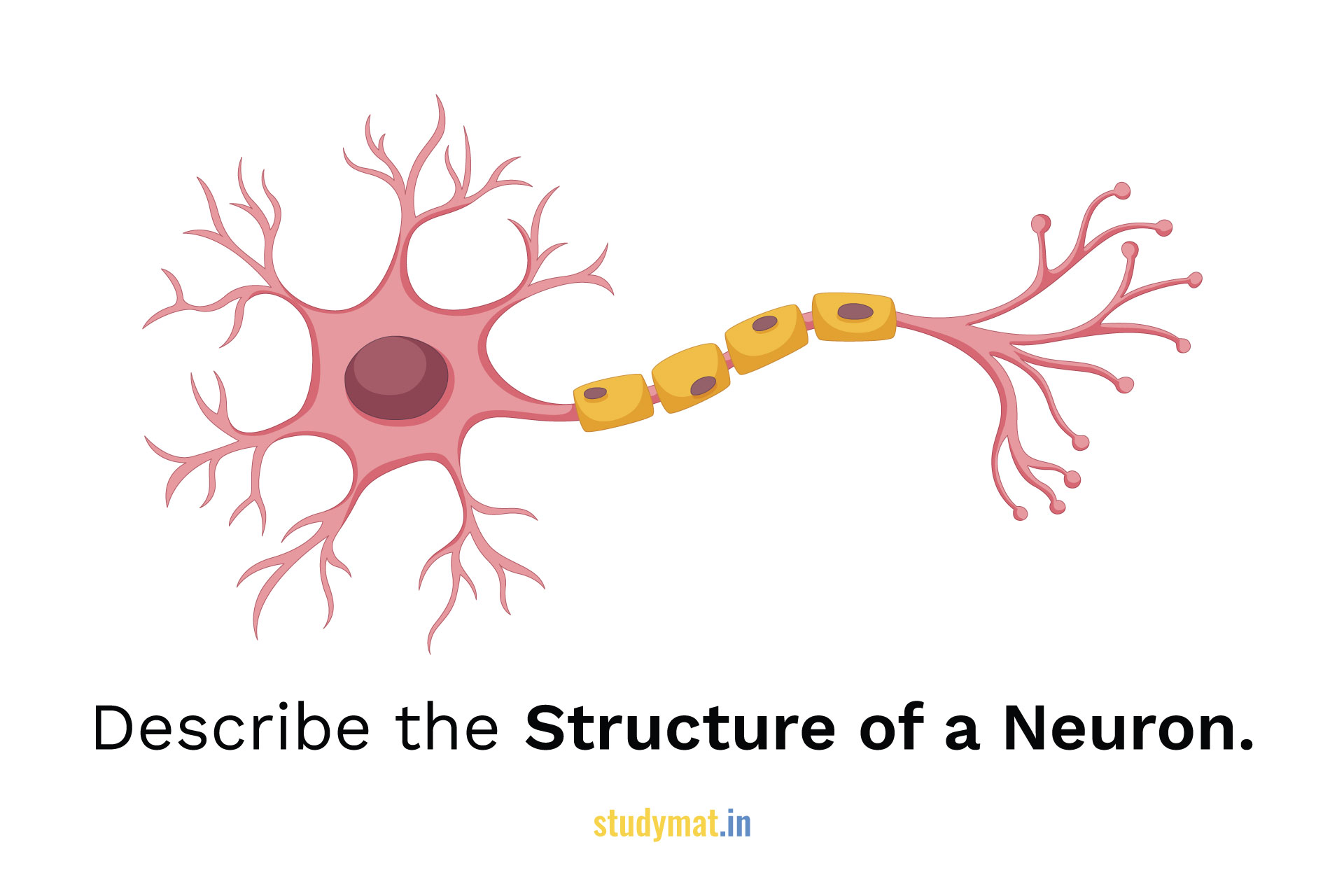

Later work, using impregnation staining and culture techniques, elaborated on Deiters' findings. Although early workers described the neuron as a globular mass suspended between nerve fibers, the teased preparations of Deiters and his contemporaries soon proved this not to be the case. The neuron is the most polymorphic cell in the body and defies formal classification on the basis of shape, location, function, fine structure or transmitter substance. However, this picture does not hold true for many neurons. This impression stems from the older work of Purkinje, who first described the nerve cell in 1839, and of Deiters, Ramón y Cajal and Golgi (see ) at the end of the nineteenth century and the early twentieth century. The stereotypical image of a neuron is that of a stellate cell body, the perikaryon or soma, with broad dendrites emerging from one pole and a fine axon emerging from the opposite pole. General structural features of neurons are the perikarya, dendrites and axons The subtle synaptic modifications are best visualized ultrastructurally, although immunohistochemical staining also permits distinction among synapses on the basis of transmitter type. Specialization also occurs at axonal terminals, where a variety of junctional complexes, known as synapses, exist. This enormous repertoire of functions, associated with different developmental influences on different neurons, is largely reflected in the variation of dendritic and axonal outgrowth. They can be influenced by a large repertoire of neurotransmitters and hormones (see Chap. Neurons can be excitatory, inhibitory or modulatory in their effect and motor, sensory or secretory in their function. These facts alone make the neuron unique. It is known that the neuronal population usually is established shortly after birth, that mature neurons do not divide and that in humans there is a daily dropout of neurons amounting to approximately 20,000 cells. Consequently, despite an enormous literature, the neuron still defies precise definition, particularly with regard to function. It is impossible in a single chapter to delineate comprehensively the extensive structural, topographical and functional variation achieved by this cell type. From a historical standpoint, no other cell type has attracted as much attention or caused as much controversy as the nerve cell.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)